The 27th time was not the charm — and for one Chinese man it could mark the end of a lifelong quest to make it to university.

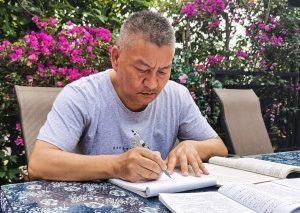

Liang Shi, 56, has tried for 40 years to get a satisfactory score on China’s national college entrance exam, known as the gaokao.

“I just admire intellectuals. I have been in awe of knowledge and well-educated people since I was a kid,” he told NBC News on Tuesday.

Regarded as one of the most challenging and competitive exams in the world, the gaokao is held once a year over two to three grueling days. Unlike in the United States and other countries where test scores are just one aspect of college applications, in China the gaokao is virtually the only determining factor in where most graduating seniors will attend university — if they get in at all.

Of the record 12.91 million students who took the exam early this month, fewer than half will gain entry into bachelor’s degree programs, based on data from past years.

Liang, a native of the southwest province of Sichuan, took the gaokao for the first time in 1983 but failed to score high enough for admission into any university, let alone his dream school of Sichuan University. In the decades that followed, he took the exam again and again for a total of 27 times, more than anyone else in China.

In the meantime he worked for a state-run factory, got married, lost his job when the company closed down in 1992 and started his own business. He was a millionaire by the late 1990s, when the average salary in China was around 8,000 yuan ($1,105) per year, according to official data.

Throughout all these years, he has never given up on the gaokao, taking it multiple times until he was no longer eligible due to his age. He started taking it again when the age limit was lifted in 2001, and has taken it every year since 2010.

In the years he was preparing for the exam, Liang said, he studied most days from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., with only a short lunch break.

“I usually started my review process in September when students start their new academic year, and continued until June, when the exams begin,” he said.

“But my timetable is not as well organized as other students’. I have so many errands, after all,” Liang continued, adding that he studied three to four hours fewer per day than high school students preparing for the exam.

Share your thoughts