A bizarre 410 million year old armoured fish unearthed in Mongolia has rewritten the history of sharks.

It shows their skeletons were once made of bone – before turning into cartilage, say British scientists.

The bizarre creature, less than a foot long, shakes the family tree by its roots.

It is an ancient cousin of modern ocean behemoths – such as the whale shark and the Great White.

Named Minjinia turgenensis, it had bony plates over its head and shoulders that acted as shields.

It roamed the prehistoric seas 170 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth.

Minjinia’s fossilised skull – dug up in the foothills of spectacular snow capped mountains – turns history on its head.

It means the lighter skeletons of sharks developed from bony animals – rather than the other way round.

Lead author Dr Martin Brazeau, of Imperial College London, said: “The fish would have probably been somewhere between 20 and 30 cm long (7.9 to 11.8 inches).

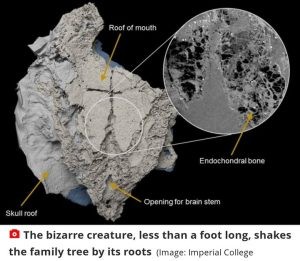

“We currently only have part of the skull roof and braincase – but the skull roof was covered in a thick bony armour.

“We know from its relationships to other similar fishes from this time it would likely have had an extensive armour on the face and shoulder.”

The animal described in Nature Ecology & Evolution sheds fresh light on shark evolution.

Whale sharks, the world’s biggest fish, can reach over 60 feet. The Great White, the largest predatory fish, grow to more than 20 feet.

Minjinia belonged to a group called the placoderms. They were the first jawed fish out of which sharks and other vertebrates – including humans – evolved.

Some turned into 30 foot sea monsters. The articulated plates also performed the function of teeth. The rest of the body was scaled or naked.

Dr Brazeau said: “So, it would superficially have looked like other placoderms. Indeed, we have found fragments of armour with a similar pattern of ornamentation to the skull roof in the same rock bed.

“These suggest there would have been bony spines sitting in front of the fins, acting as either a cutwater or a defence. However, we don’t yet have a full or partial skeleton.

“Like the vast majority of fishes from this time, it was likely predatory – but it’s not yet possible to say exactly what it ate without the direct preservation of the jaws.”

Today, sharks’ skeletons are made of cartilage – which is around half the density of bone. It was thought to be the original template before the heavier alternative.

Minjinia completely contradicts this. Cartilage is known to have come first. Sharks were believed to have split from other animals prior to the arrival of bone.

The theory was they kept the former – even though fish generally favoured the latter. But Minjinia is a shared ancestor.

It suggests sharks had bones and then lost them – rather than keeping their initial cartilaginous state for over 400 million years.

Dr Brazeau said: “It was very unexpected. Conventional wisdom says a bony inner skeleton was a unique innovation of the lineage that split from the ancestor of sharks more than 400 million years ago,.

“But here is clear evidence of bony inner skeleton in a cousin of both sharks and, ultimately, us.”

When we are developing as foetuses, humans and bony vertebrates have skeletons made of cartilage – like sharks.

But a key stage in our development is when this is replaced by hard ‘endochondral’ bone that makes up our skeleton after birth.

Previously, no placoderm had been found with this. The skull fragments of Minjinia were “wall-to-wall endochondral”, said Dr Brazeau.

It points to a more interesting history for sharks.

Explained Dr Brazeau said: “If sharks had bony skeletons and lost it, it could be an evolutionary adaptation.

“Sharks don’t have swim bladders, which evolved later in bony fish, but a lighter skeleton would have helped them be more mobile in the water and swim at different depths.

“This may be what helped sharks to be one of the first global fish species, spreading out into oceans around the world 400 million years ago.”

Sharks are remarkably resilient. They’ve survived all five global mass extinctions that knocked 80 percent of the planet’s mega-fauna out of existence.

But tracing their evolution is frustrating as fossilised cartilage does not preserve as well as bone.

The researchers still have plenty of other material collected from Mongolia to sort through – and perhaps find similar early bony fish.

The placoderms thrived for almost 60 million years – a period dubbed the ‘Age of Fish’.

They were wiped out in a mysterious mass extinction event 359 million years ago – 120 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth.

Last month a study suggested it was caused by radiation from an exploding star 65 light years from Earth.

Share your thoughts