Goal speaks to the Germany ace’s family, former coaches and team-mates to explain how a shy kid from Gelsenkirchen became a world-class midfielder

It all started the way many other kids start off: a courtyard, a garage door and a football.

Every day after he had finished his school work, Ilkay Gundogan would spend the afternoon playing outside, but sometimes his practice was cut short by angry neighbours annoyed by the thud of the ball against the garage door.

“There was a man living in the neighbourhood who would occasionally shout down from his balcony: ‘F**k off, kid, I’ve got the night shift coming up.’ Then, of course, the afternoon was over,” says Rainer Konietzka in an interview with Goal.

Konietzka was the first chairman of local club SV Hessler 06, where Gundogan had played since he was just four years old. As well as playing for the local club in Gelsenkirchen-Hessler, Gundogan took every opportunity he had to play football.

His grandfather had moved to the Ruhr area from Turkey in 1973 to work as a coal miner, but the family still had a strong love for Turkish football and used to watch their team every week.

“Our fathers were huge Galatasaray fans. We followed almost every game,” his cousin Ilkan Gundogan tells Goal . “That was always the highlight of the week for us.”

Before and after those games on television, Ilkay and Ilkan would play outside, pretending to be their footballing heroes.

“Gheorghe Hagi was one of our favourite players in the beginning,” says Ilkan. “But later, Ilkay had another favourite: Kaka.

“Our family never forbade us to play football. Even if we came home with dirty clothes or grazes, we didn’t get in trouble. And when the weather was bad, we went in and made balls out of socks and played with them. Football was everything.

“There is always that one player you choose first when you get together with some boys to play football. For us, it was Ilkay.”

In training and on the pitch at SV Hessler 06, Gundogan’s quality was clear to anyone who watched.

“At first, some coaches said he was too small, but his technique was exceptional even at a young age,” Konietzka recalls.

Gundogan was determined to succeed and decided to join SSV Buer, having been overlooked by Bundesliga side Schalke despite spending a season at the Gelsenkirchen club.

“There were frequent Schalke scouts at our training ground to have a look at Ilkay,” Konietzka reveals. “To put it sarcastically, they did a terrific job, as they so often do, by first bringing the boy in on a trial basis and then sending him away again.”

When Gundogan recalled the experience for the Players Tribune earlier this year: “Schalke let me go. Or, to put it the way I felt: They grabbed me by the collar and threw me out the door.”

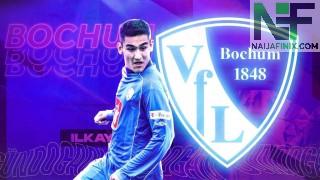

After impressing at Buer and Bochum, Schalke came knocking again but Gundogan had not forgotten how they had treated him when he was eight years old.

“I only heard about it in passing,” reports cousin Ilkan, “but I know that Ilkay was very disappointed with Schalke. It shows strength of character that he didn’t go there again.”

At Bochum, he met Michael Oenning, who worked as the club’s Under-19 coach between 2007 and 2008 and later went on to coach both Nurnberg and Hamburg in the Bundesliga. Gundogan credits him as one of the most important people in his career.

“The first contact was actually on the football field,” Oenning tells Goal . “In the first training session with the new team, I had them play a kind of football-tennis over a longer distance.

“Ilkay played incredibly good volleys with both feet. I noticed that right away. I then grabbed him and asked him if he could also play these long passes from the ground. He also did a great job with this task.

“After training, I went up to him and asked him what his name was. When he told me his name, I said to him: ‘I think you’re going to be a professional footballer.’

“Ilkay looked at me with wide eyes and didn’t want to believe it at all. But he had inspired me so much in training that I just wanted to give him that feedback.”

Gundogan’s impact at Bochum saw him score 14 goals in 24 games for their youth side to earn a call up to Germany’s Under-18 squad.

Off the field, Gundogan’s family played a big role and wanted him to have an education to fall back on if his dream of being a professional footballer did not work out.

“Ilkay’s father was still a bit suspicious about the whole thing, that his son was on his way to becoming a professional footballer,” says Oenning. “At the beginning, he probably would have preferred him to become a businessman or something like that.”

As a result, earning his school-leaving certificate and graduating from high school was just as important as his footballing development.

Bochum were not able to properly balance football and school, though, so Gundogan contacted Oenning, who had moved to Nurnberg, and asked his former coach if he could follow the same path.

Not only was Nurnberg able to get Gundogan into the local Bertolt-Brecht-Schule (BBS), but the new club proved better from a sporting perspective as well.

At the BBS, he came to the attention of headmaster Harald Schmidt, who still has a good relationship with his former student.

“Ilkay was already a young man back then who was very disciplined and knew exactly what he wanted,” Schmidt tells Goal .

“He came from a home where education was very important, and a lot of emphasis was placed on Ilkay getting a good school-leaving certificate in addition to his football education.

“It was always a pleasure for me and his other teachers to work with him. Regardless of his positive character traits, Ilkay was a very bright student.

“A number of Bundesliga players and Olympians have passed through our hands – but Ilkay is one of them who will always be remembered. He is a very special person as a human being.”

Oenning initially used Gundogan sparingly at Nurnberg as the teenager got used to life in another new city, only playing him in the last game of the season as a substitute.

Nurnberg were promoted to the Bundesliga, but Gundogan made such an impression in pre-season training, it was impossible for Oenning to leave him out any longer, even with the club now preparing to fight for survival in Germany’s top flight.

The first game of the season saw the 18-year-old Gundogan score his first goal for Nurnberg in a 3-0 cup win over Dynamo Dresden and he was selected in the starting XI the following weekend as they kicked off their Bundesliga campaign against Schalke.

“There is a regular pub in Nurnberg for the really hardcore Nurnberg fans,” says headmaster Schmidt. “After Ilkay’s first appearance, a hardcore club fan came up to me and said: ‘This Ilkay Gundogan, he goes to school with you, right? He’s going to be a really, really big player.’”

He quickly became a regular in the starting XI, playing 90 minutes of four of the first seven league games in 2009-10, providing his first Bundesliga assist in the clash with Bayern Munich.

However, an injury ruled him out for a month and a half, and Nurnberg’s form declined. After just three wins by the winter break, Oenning was fired as head coach and replaced by Dieter Hecking.

Although Gundogan had been Oenning’s protege, the new manager quickly saw his talent and continued to pick him regularly.

Gundogan’s first Bundesliga goal followed, against Bayern, and Hecking was able to guide Nurnberg out of the automatic relegation spots and into the playoff, where the young midfielder scored in the second leg to help keep ‘Der Club’ in the top tier.

At the BBS, Gundogan’s performances for Nurnberg had made him a minor star, especially with his younger schoolmates.

“We once had a conversation in my office. I don’t even remember exactly what it was about,” Schmidt describes.

“When we had finished the conversation, he asked me if he could stay five minutes longer. I said: ‘Sure, can I offer you another coffee or something else? Why do you want to stay longer?’

“He said: ‘I would like to wait for the end of the break.’ He liked to sign autographs, but he was rather uncomfortable about it because of his quiet nature.

“This reticence was typical for him. He had no airs and graces then and still has none today.”

Gundogan’s down-to-earth personality was also seen at his football club, where he made new team-mates feel at home.

Julian Schieber had joined on loan from Stuttgart the season after they stayed up and quickly became friends with the Germany underage international.

“I met Mehmet Ekici at the car park, he was also a new player on loan and was waiting for Ilkay,” Schieber tells Goal. “Ilkay gave us both a warm welcome right away.

“His family’s hospitality helped me a lot to settle in Nurnberg. Ilkay’s front door was always open for family and friends. I was welcome from day one and felt at home.”

Nurnberg’s young trio catapulted them to an incredible sixth place in the Bundesliga, with Gundogan scoring five league goals along the way. It remains their best-ever finish in the league and they are now, unfortunately, back in Germany’s second tier.

During that 2010-11 season, Gundogan successfully passed his exams and left with his school-leaving certificate.

“When he had the certificate in his pocket, he invited all the former teachers out to eat Italian. That was a wonderful evening with great conversations,” says Schmidt.

“Afterwards, I asked him if we could do a symbolic jersey exchange. He got a jersey from our school, and the school got a jersey from him in return. It was a special moment and that jersey has a place of honour to this day.”

His on-field exploits had not gone unnoticed either. Borussia Dortmund and Hamburg came calling, with the former signing him for around €5.5 million (£4.8m/$6.7m) in the summer of 2011.

“I actually wanted to get him to Hamburg, it was a pretty tough battle,” reveals mentor Oenning. “He had to make a decision. He chose Dortmund. Thank God…”

source:- goal

Share your thoughts