It is said that strength comes in numbers, and that is what award-winning food producer Angharad Underwood found during the pandemic.

When Covid-19 hit last year, Ms Underwood was faced with having to temporarily close her business, The Preservation Society.

Based in the Welsh town of Chepstow, right beside the English border in south east Wales, she makes jams, chutneys and other preserves.

With other local food producers in the same precarious position, 25 of them decided that instead of shutting up shop, they would pool their resources and join together.

So in May 2020 they formed the Wye Valley Producers cooperative.

“It’s likely that many of us would have furloughed for the duration otherwise,” says Ms Underwood.

“Instead, we had people to lean on – guidance, encouragement and ideas. We realised that by joining together we could make a difference.”

As mentioned, Wye Valley was set up as a cooperative. But what exactly is that? Put simply, it is a business that is owned by its members and democratically run.

It could be, as in the case of Wye Valley, a group of small firms that come together. Or it may be a collective of self-employed workers who run a single business, or even a larger retailer – such as the Co-Op supermarket chain – whose members include millions of its customers who have signed up.

The common factor is that there aren’t any external shareholders, and profits are either reinvested, or shared among the members.

It all sounds a bit old-fashioned, and the co-operative movement was indeed founded in the 19th Century. But there are today more than 7,000 co-operatives in the UK, and a whopping three million around the world.

Many, both within the UK and elsewhere, say that being a co-operative has made them more resilient to the pandemic than if they had been stand-alone, standard businesses.

At Wye Valley Producers, Ms Underwood says members spend many hours on Zoom calls, helping each other: “It isn’t just about the money, but sharing skills and knowledge, with people in the same boat.”

The International Co-operative Alliance (ICA), the global organisation that represents the movement, says that this increased coming together in response to Covid-19 has been replicated around the world.

“Online meetings and webinars were organised by cooperatives across the world,” says ICA director of legislation Santosh Kumar. “The international exchange of practices and resources has been widespread.”

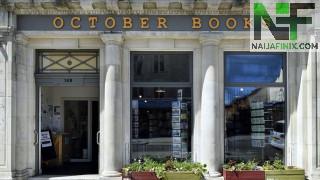

In Southampton, cooperative shop October Books has been trading since 1977. In addition to books it sells vegan food, vegetables and ethical cleaning products.

October Books says that thanks to support and advice from Cooperatives UK, the organisation that represents the movement in the UK, it had the knowledge and confidence to adapt to the new situation.

“Being a cooperative meant we could have difficult conversations about what was best for the shop as a team,” says Ms Diaper.

October Books and its 103 members decided to keep the shop open, but temporarily furlough four of the eight permanent staff. “The decisions to furlough workers and reduce opening hours were made collectively,” adds Ms Diaper.

Across Europe in Croatia, women-led cooperative Brlog Brewery has been making a range of beers since 2016.

“When the pandemic hit, first we were in shock because we had made a lot of beer,” says co-founder Ana Teskera.

“Suddenly, it was all stuck at the warehouse. There was potential that we would [lose it] and wouldn’t get paid for the goods already sold.”

The brewery’s six directors, and 90 cooperative members, who include volunteers and customers, came up with a plan – they would shift from selling to bars and shops.

“[Instead] we sold most of the beer through the coop network, distributing direct to members, and even had to produce more,” says Ms Teskera.

It was so successful that last summer the brewery, based in the coastal city of Zadar, moved to a bigger facility.

“We learned a lot, made great changes, kept all our employees – even added a new one,” says Ms Teskera. “The team is more connected now, strong and happy to go forward.”

In India, an organisation called the Self-Employed Women’s Association (Sewa) has helped female workers form cooperatives since 1972.

Now with more than 1.8 million members, Sewa offers them advice and support on everything from business finance to expansion and marketing.

“The pandemic has been a double whammy for our members,” says Sewa senior coordinator Salonie Muralidhara Hiriyur. “It has disrupted health and livelihoods on a massive scale. Some sectors of work, like domestic work and childcare, came to a complete halt.”

To help its members find new income opportunities during the pandemic, Sewa ran training classes via WhatsApp video calls, including one on how to manufacture face masks.

Rehat Rangrez, a member of a handicrafts cooperative called Abodana Mandali, took part. “I then started training other women in the cooperative on how to make masks too – all on video calls,” she says.

She and her “fellow cooperative sisters” went on to make 20,000 masks in just three months. Because of this work, Ms Rangrez had enough income to support her family.

Gabriel Burdin, associate professor in economics at Leeds University, says that cooperatives generally cut jobs a lot less.

“In conventional business, layoffs are the most frequent cost-cutting strategy,” he says. “Cooperatives adjust along other margins, such as pay cuts or work-sharing arrangements. Cooperatives share the consequences of a crisis among their members.”

However, Prof Burdin also cautions that cooperatives do come with their own risks, especially those where the members and owners are the workers.

He says that such people are in the position where they invest their own money in the business that they also work for, and are paid by. So if the business fails, they lose both their wages and any money they have invested.

“By providing labour and capital to the same company, they are putting all their eggs in one basket,” says Prof Burdin.

Looking ahead, Cooperatives UK is now continuing to gather evidence for its 2021 Coop Economy Report into the sector. It says early indications show new cooperatives are still being formed and fewer have closed than in previous years.

“[And] we know that before the pandemic, new start coops were nearly twice as likely to survive their first five years than other types of businesses,” says Cooperatives UK chief executive Rose Marley.

Back in south east Wales, Ms Underwood says that Wye Valley Producers – which has members from both sides of the border – is now considering a delivery service: “And we can’t wait to do events and courses, we have some great ideas up our sleeve.”

Share your thoughts